The scene at the Pece stream is bucolic: tiny patches of algal blooms float on a stream of water that seeps through clumps of elephant grass, breathing new life into the wetland.

But in recent years, the wetland has continuously battled pressure from all sides— buildings have been erected right at its edge, crops are cultivated and wastes are dumped there, and there have been repeated attempts by a local businessman to build a petrol station on this wetland.

In Uganda, wetlands are often looked at as desolate, wasteland areas. Statistics from the Ministry of Environment show that wetland coverage was at 15.6 percent (37,000 sq. km) of the country’s total surface area by 1995, and by the year 2015, 8.4 percent (20,000 sq km) wetland surface coverage was lost.

Yet the mushy grounds are sources of livelihood—ranging from fishing, medicinal plants, and craft materials, you name it— to more than five million Ugandans. Add to that, wetlands also capture planet-warming carbon (greenhouse gasses) to regulate climate change as well as controlling floods and sustaining aquatic life.

The Ministry of Water and Environments is concerned that many Ugandans are at risk of losing out on these benefits if they fail to punish encroachers.

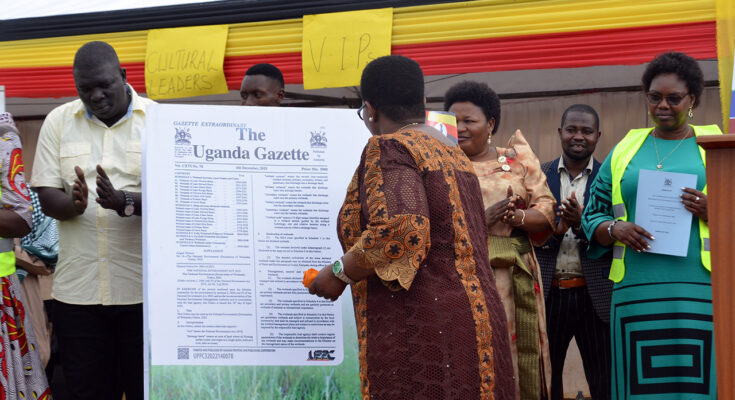

While commemorating World Wetlands Day in Gulu City recently, Stephen Mugabi the Director of Environment Affairs at the Ministry of Environment, noted that there is a “tendency of some people hiding boundaries of wetlands” and therefore the government had to gazette wetlands to ensure that they are protected from encroachers.

The other issue, he worried, was the slow pace at which the courts handle environmental cases, urging that “there needs a special court that can deal with these issues directly”.

The environmental cases “sometimes last more than three years,” Mugabi noted at the same event where the first-ever national gazette for wetlands, detailing clearly marked 8,613 wetlands, covering 33,762.6 sq. Km was, also launched.

The gazette, he said, “…is meant to help the government to tell the public where every wetland is located…we are no longer in that era where they have been asking us where the wetland boundary is, and we keep quiet”.

The bright spot, however, Mugabi highlighted that there is significant progress where 352 sq.km of degraded wetlands have been restored back and 2,100 km demarcated. The government targets to demarcate 5,000 kms of wetland boundaries across the country by 2025, he added.

But some leaders argue that this progress can be maintained only if the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), a body responsible for protecting wetland management, avoids “segregation” when arresting wetland encroachers.

“I have had issues with NEMA [in Gulu],” she said. “Those who play with the wetlands are mainly the rich who consider themselves the untouchables… They should all be arrested because some of them have the audacity to change the mark stones”. (In Gulu district, 37 percent of wetland has so far been degraded.)

Meanwhile, experts like Decimon Anywar, a Gulu-based environment scientist, advise the government to go beyond gazetting wetlands by conducting more sensitization outreach sessions on the importance of wetlands.

“People need to learn the importance of wetlands,” he said. “Every time they cultivate in the wetland, they destroy their integrity – water dries up because there is no watershed and therefore water is exposed directly to the sun while some people use pesticides when cultivating and this pollutes the wetlands”.

State Minister for Water, Aisha Sekindi, revealed that the Environment Ministry had revoked 302 land titles on Kinawataka wetland in a recent pilot study conducted in Kampala, adding that the same approach will be replicated in various parts of the country.