Every truck of charcoal en route to Kampala from Northern Uganda is bonded to a coordinated money-making gang that is perpetually dismantling the forest cover in the region.

The commercial charcoal dealers who later joined the illegal trade are unsustainably wiping out trees in most villages as well as the protected 1,259 hectares of Zoka Central Forest Reserve.

At the edge of Adjumani district, approximately 7 kilometers North-West of the present-day Apaa land, Zoka Central Forest Reserve with endemic flying squirrels, birds species and plant varieties has been invaded by the illicit traders in forest products, risking both fauna and flora.

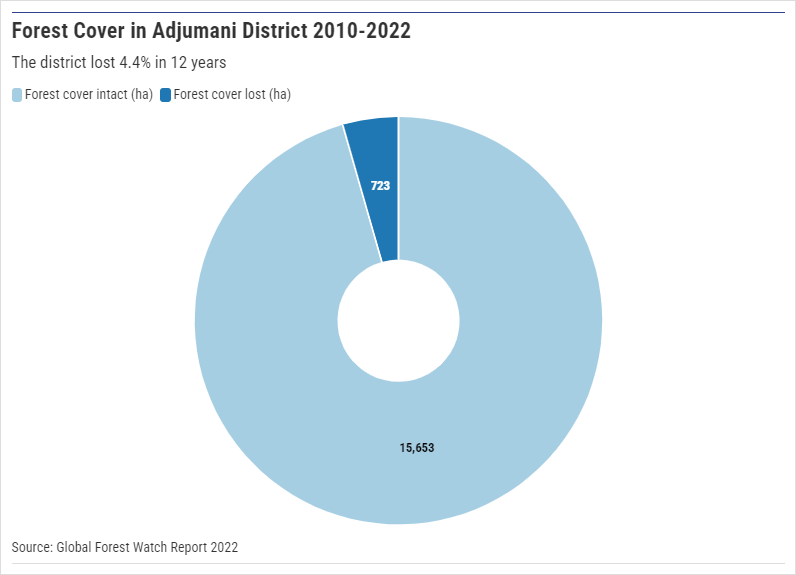

The 2022 report by Global Forest Watch revealed that, in 2010, Adjumani had 16376 hectares (ha) of tree cover, but in 2022, it had lost 723 hectares of the tree cover, an equivalent to 322 kilotons of carbon emissions in the district.

Adjumani lost an estimated 4.4% of its forest cover in the last 12 years, this means, that with the current illicit trade in its forest products, without realistic interventions, the losses are likely to double and expand to engulf the remaining 15,653 hectares of the forest cover.

The losses are attributed to illegal logging, charcoal business and high demand for charcoal and firewood due to the influx of refugees from neighbouring South Sudan to Adjumani district.

Currently, the road towards Zoka is always crammed with motorcycles ferrying bags of charcoal to waiting heavy boxed-bodied trucks, that later transport them to the central part of Uganda.

The cyclists each transport three bags of charcoal into the different camps of dealers ready with trucks for shipments.

Although a team of policemen always stand a few meters away from the trade, the dealers calmly receive bags of charcoal from Zoka and pack them before setting off, leaving a cycle of this coordinated ‘ecological crime’

The networks of the middlemen in the charcoal production value chain

A recent random survey into selected charcoal loading camps vividly uncovered the networks of people who have positioned themselves in the corridors of this black market of charcoal production value chains in Northern Uganda.

At the entry of one of the camps, bags of charcoal led us to where three men sat. One of them quickly got up to identify us and our interests.

“Where are you from and how can we help you?” he asked, signalling us to sit beside him.

We introduced ourselves as charcoal dealers from other camps in need of their urgent support.

A day before, the Centre was attacked by unknown men armed with arrows, who were overpowered by the police with live bullets. Although the natives of the area were still in panic, the dealers seemed unbothered.

“I am not involved in their conflict. Those people come to look for their enemies. I am not their enemy,” declared Swaibuh Mukiibi, the man we were directed to, to drive us through his networks.

Within the area where charcoal is produced, there were reports of attacks, some people were killed, others were injured in an alleged tribal conflict between the Madi and Acholi, the dominant tribes in the area, each claiming the ownership of the disputed Apaa land, so, Mukiibi waits at the camp with money in his bag.

“I fear and I can’t go there in the first place to look for charcoal. They bring here using boda-bodas, even tractors can bring,” Mukiibi revealed.

A few minutes into the camps, the cyclists were bringing in charcoal. Each bag was paid for by the dealers at 30,000 shillings before the dealers found an escape route to Kampala, where more negotiations began with forces on the highway.

Police find itself at the center of the illicit trade

Whenever a truck is full, the coordination starts with ‘secrecy’ involving the law enforcers on the roads through brokers. Taking a truck out of the villages to Kampala means, ‘cleansing’ the roads. Sources divulged that from the villages, every truck pays an average of 100,000 Uganda shillings to police on duty, besides other checkpoints.

“Transporting a truck of charcoal from here to Kampala costs us 4 million shillings. But God must be in control. Sometimes you pass, other days they may impound your truck. God knows and He is in control,” said Mukiibi.

How the deal works

At the helm of the trade is ‘William’, the principal name that every dealer connects to for safety. The dealer Mukiibi also connected us to him (William) for the same reason, security.

Getting connected to Willaim, he, (Mukiibi) first referred us to a woman in her 40s, “I have his contact but my phone is off; the other woman there also has it, go to her, she will give you his contact” Mukiibi stood up, directed us and stepped back to his camp.

On reaching her, she only introduced herself as Hida picked up her phone, checked through William’s contact and rang him, the phone was on loudspeaker, “William, you have a new customer with us here.” William first laughed then answered; “Give him my contact, give him my contact,” Willaim could be heard speaking on the phone through a loudspeaker.

Before the two could end the conversation, two cyclists arrived at her camp with 6 bags of charcoal, she (Hida) cut off the call and handed us a small sheet of paper with William’s contact attached to it. “Call this number, he will help you,” she hurriedly went to receive those cyclists.

This Publication established that each boxed-bodied truck moves with 350 bags of charcoal and it requires one to invest 4 million shillings for “clearing” the road. The money is received without acknowledgement of the receipt by the law enforcers.

To cut the costs of road clearance, each truck has at least three dealers who contribute money to the brokers stationed on the lookouts at the checkpoints.

The money solicited is allegedly deposited to the mobile money of the officers deployed at the different checkpoints. The broker goes ahead each time and provides the number plate of the truck whose dealers have paid for road clearance.

But those who default either pay extra money or have their trucks impounded. This is where ‘William’ the broker is pivotal in acknowledging clearance for the roads.

Once the road clearance is completed, the broker notifies the dealers and the truck leaves the villages for Kampala.” Sir, I am done, you go, the road is clean” Dealer Mukiibi recounts.

With the syndicate involved, trucks are examined at each of the checkpoints before they proceed to Kampala. If a broker is involved, each truck pays 200,000 shillings, but for traders without connections, the cost goes above 500,000 shillings. In other instances, such dealers will have their trucks impounded and charcoal auctioned.

Dealers set own price of charcoal in Kampala

The road clearance comes with a high price paid by the final buyer either in Kampala or any other places where charcoal is sold.

Upon reaching the final market, the dealers determine their prices making sure they recover the expenses they incurred on the roads.

For instance, a bag of charcoal in Kampala is sold between 85,000 shillings and 100,000. Each truck that carries 350 sacks of charcoal is hired at 4 million shillings.

The bags of charcoal are bought at 10.5 million shillings, implying that a dealer can amass between 28 to 31.5 million shillings per truck.

Once all expenses have been deducted, the dealer remains with between 10 to 13 million shillings as profit, hence, attracting more people to this lucrative deadly business.

“Would I be here really if there was no profit”? Let me tell you, in Uganda, people are working for food, food only! and I don’t need to tell you this. You open up a business in Kampala, the Uganda Revenue Authority will look for you, and the landlord will again charge you highly, so where is the money? Ugandans are so poor and nobody should tell you this,” Mr. Mukibi said.

A week-long thrill with ‘William’ the broker

‘William’ secretly connects his clients before offering them immunity on the roads from the villages in Northern Uganda to the final markets.

Through a telephone number given by his team operating on the ground, we rang him a week later and introduced ourselves as part of those who needed his urgent support. “You mean you were from Apaa,”? he could easily reconnect and carried the deal on.

The purported deal involved the transportation of 250 bags of charcoal in the neighbourhood of Apaa. “The bags aren’t enough for a boxed-bodied truck. Talk to your colleagues to add you more 100 bags so that you can avoid high costs on the roads and once you have it ready then call me,” as he hung off the phone.

Three days later, we reached him again with the assurance of the additional bags fitting a truck,

“Have you loaded the truck?” he asked,

“Yes, Sir.”

“Where are you exactly?”

“Ober-Abic, a few kilometers East of Apaa.”

But his probing and wary questions continued.

“Where does the driver come from? Is he from Buganda?”

“No, he is from Eastern Uganda,” we responded.

Although he was curious, we requested to call him later, as it was threatening to rain. He consented and we used the moment to request the driver whom he wanted to speak to. Fortunately, his (driver’s) accent matched William’s. We called him the following evening to continue the deal.

The amount of money William asked us to pay to pass the checkpoints and the amount other dealers told us we would pay was the same.

The deal concluded and William gave us a mobile money number to deposit four million shillings. He assured us that the money would be shared by the personnel at checkpoints for clearance. Surprisingly, the number given was registered under a different user name.

He quickly checked his account to confirm receipt of the cash.

“It’s getting late and you need to leave now. But remember I first have to clear the road for you. Hurry and pay.” We parted ways. But at this point, I imagined how William would bag millions of shillings only a few know about after road clearance.

Has the eviction of the migrant cattle keepers overshadowed the ban on charcoal business?

With an increasing commercial charcoal business threatening the survival of trees in most villages from the North, President Museveni issued a ban on trading in forest products. The ban contained in the Executive Order number (3) of 2023 was to further ban the ‘indiscipline’ migrant cattle keepers from grazing animals in the North.

However, the Minister for State for Northern Uganda, Grace Freedom Kwiyucwiny, acknowledged that the gaps in the implementation of the directive against charcoal trade have been overlooked, as the security is facing the dilemma of evicting the errant migrant cattle keepers for unlawfully occupying the region.

“At the moment we can’t do much as you know we have a big problem of evicting the indiscipline Balaalo. But I will follow up with the Ministry of Water and Environment to ascertain the progress of curtailing this indiscriminate tree cutting from the region,” Kwiyocwiny told Journalists recently.

On December 5, 2023, a security team and technocrats from Amuru district intercepted a boxed-bodied truck with charcoal belonging to one Jassi Nakasitu, a resident of Capital Kampala, when her truck had already left Apaa trading Centre from Adjumani district to Kampala.

The single mother whose business collapsed from South Sudan due to inflation, had to borrow a bank loan and risk it in charcoal business, owing to its profitability.

Nakasitu’s plea with the team to have her truck released fell on deaf ears, and the impounded charcoal was auctioned by the National Forestry Authority, to Mukiibi, traders like Nakasitu, who failed to comply with the “road discipline” (paying clearance fee), end up having their trucks impounded.

‘’I have already injected 13 million of the 20 million I borrowed from Centenary Bank to come here and start this business. I put my only house as security with the Bank, and I will lose it if I fail to pay back this loan,” a teary Nakasitu pleaded with enforcers as her truck of charcoal headed for auction.

Inside jobs at the National Forestry Authority (NFA)

As trees get depleted, the management of the National Forestry Authority faces internal problems, which officials blame on poor governance of the natural resources in the region, corruption, understaffing and lack of logistics for field operations.

John Giribo, Manager of Aswa River Range, disclosed that the team is challenged with monitoring a vast area with 83 forest reserves in the region, adding that the enforcement team only gets 400 litres of fuel which does not take even half a month, the weak link the players have manipulated to deplete the forests.

“The area is big and we can’t cover every single reserve in a day. You are here this week, and you don’t know what is happening in the other reserves. This becomes a problem of understaffing and logistical support,” said John Giribo, the Manager, Aswa River Range.

But the main challenges according to Giribo are that individuals who are deep in the villages sell off their lands to people who go on the pretext of opening farmlands but descend on the trees for charcoal, and the local governments continue to generate revenue from the forest products despite the ban.

“When I go out to the field, I still find local government officials with movement permits being issued to the transporters,” Giribo said.

He said the dealers are operating in powerful groups and have gone on to single them (forestry officials) out individually, and that’s why they need many stakeholders involved to fight this vice together.

Charcoal vis-a-vis poverty

Dealers in forest products argue that the government must provide the population with alternative energy sources if the ban on forest products is to be impactful.

“Who can afford electricity in this Country if not few? Look at that grass-thatched house if that old woman standing in the compound can afford gas for cooking. Let there be no charcoal for just one week in Uganda and see how poor people are,” Mukiibi observed.

The Uganda Electricity Regulation report of 2020 shows that only 45 percent of the citizens are connected to the national power grid, this increases the vulnerability of the bigger population who turn to affordable and reliable charcoal as fuel for cooking.

The Uganda National Household Survey of 2016-2017 revealed that up to 90% of the citizens use burned dry wood for fuel with 15.5% of the charcoal consumed in the rural areas compared to 66.4 percent in the urban areas and cities. This leaves charcoal as the most affordable and reliable source of domestic energy.

The charcoal industry produces a projected 400,000 tons of charcoal annually, but the largest portion with 300,000 tons is locally consumed in the Capital Kampala according to the 2016 report by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development on the national survey on charcoal production.

The study whose finding was published in June 2016 was conducted from 990 institutions which included schools, hospitals, hotels, barracks prisons and industries which presented charcoal as the most common energy source used in the country.

About 837 metric tons of charcoal are supplied to households in Kampala alone per day during a dry season but the consumption scales up to 1,017 metric tons during the rainy season, meaning, without alternative energy sources, more trees have to be cut down from the Upcountry sides to feed Kampala during winter than summer.

The survey mapped out central Uganda as the biggest supplier of charcoal in Kampala at 40.9% followed by the northern region whose supply at the time of the reports stood at 39.5% but the region is currently battling with the infestation of dealers mainly from central and other parts of the country and from the daily shipments, the percentage could surpass the latter.

Uganda is estimated to have a forest area of 2,347,400 hectares in both private and protected areas depicting 9% of the Country’s total land area but charcoal produced from privately owned forest accounts for 43%, central forests 22%, on-farm trees at 20% while others stood at 14% as the reports further revealed.

From 2001 to 2022, Uganda lost 1. 763,000 million hectares of tree cover. Previously, the Country’s Forest cover was at 6.93 million hectares covering 29% of the land area but in 2022, the sizable land area with trees reduced by between 9% and 13% only.

Uganda environmental degradation alerts

The Global Forest Watch report of February 2024 shows upward trends in deforestation alerts in an area of approximately 257 hectares of land in the Country. Between February 5 and 12, 2024, there were 3,507 fire alerts reported in Uganda but the Country lost its 267 hectares of forest cover alone to fire on top of other drivers of the forest cover loss.

The top five hit districts include Lweero where its destruction stands at 39 hectares followed by Adjumani with 31 hectares, Mukono at 22 hectares, Masaka and Mpigi at 17 and 16 hectares respectively.

Despite the mass destruction of forest covers across the Countrywide, the Global Forest Watch notes that there has been some progress in the tree cover gain between 2000 and 2020 with Mubende topping with 18.8 hectares, Masaka 9.77 hectares, Kiboga 9.65 hectares, Masindi 8.56 hectares and Busenyi with 7.49 hectares.

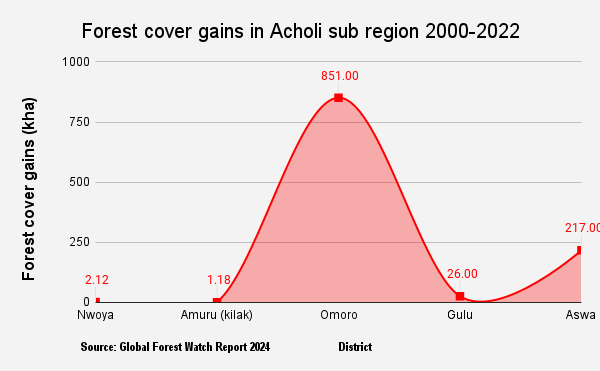

However, the restoration progress from West Acholi districts stands at 1,097.3 kilo-hectares (Kha) cumulatively by December 2022. In Omoro district, progress stands at 851Kha hectares, Amuru 1.18 Kha, Nwoya 2.12 Kha and Gulu which includes Aswa at 243 Kha.

Similar data from the National Environmental Management Authority revealed that, since 1900, the Country registered a net gain in forest cover from 9% in 2017 to 13% in 2020 in contrast to the forest cover loss of 37.1%, around 1.763,000 hectares between 1900 to 2010.

Herbal medicines bringing back to life endangered tree species

Amidst the destruction of tree cover in the land stands a group of women who are fighting to restore sanity to mother nature mooting a campaign for voluntary household tree planting.

Every time a tree is pulled down by a power saw for either logging or charcoal production, Julliet Adoch would think of where her next plants for healing would come from.

Some call them native doctors, others refer to them as ‘witch doctors’ but the herbalists in their umbrella body, Wise Women Uganda do not only rely on the forests to harvest fuel from but nature has been keeping the plants to derive human healing from.

The leader of the group Juliet Adoch, who is a Botanist and Agro Forester from Makerere University disclosed in a recent interview that each of the households was supported with between 200 to 800 seedlings for revival of the tree cover which were destroyed in their area.

From the existing trees, the team have now ganged up on manufacturing herbal medicines and selling, but 40% of their earning is saved to raise seedlings which are distributed to the community.

The tree planting kicked off in 2020 in the areas of Unyama, Bungatira and Owoo, all in Gulu district reportedly reached out to 1473 families targeting mass planting of Shea trees, Afrizella Africana, mahogany and other’ sacred trees’ which previously provided herbal medicines.

“There is no healing and life without proper control of the environment but it’s the women who suffer most when trees are no more. We make medicines out of these trees but we also use them for wood fuel” Adoch told this Publication.

At least 40 vigilante women have been trained in each of the districts across the Acholi subregion, according to Adoch, their work is moving door-to-door within their villages to motivate peers to embrace this self-campaign of reforestation.

The mother nursery bed established in Bungatira Sub County is where seedlings will continuously be raised from and distributed to households. A ‘wood farm’ is also established on a 7-acre piece of land to support the manufacturing of herbal medicines.

“We are raising money from traditional medicines to finance this campaign and we hope to bring more women on board to help us fight this injustice” She added.

Similarly, environmental youth activists from the region have stepped up the fight against the illegal logging and charcoal business, through their umbrella body Acholi Conservation Agency, the group have recruited volunteer youths, 10 from each of the districts in the region to sanitize the community on the importance of conserving trees in this part of the Country.

The environmental youth-led activist Christopher Oruka is optimistic that activism amidst other interventions is helping to reduce indiscriminate tree cutting in the region, for instance, in Gulu, some of the reformed charcoal dealers have started planting trees to replace what they cut.

“Some have started other businesses while others have started planting trees in the area they have destroyed before; one has come out voluntarily and planted five acres of trees where he cut them before so let there be more sensitization but also alternatives for energy” Oruka said.

Government reveals plans to reforest the North

Alfred Okot Okidi, the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Water and Environment noted that the reckless harvesting of trees for charcoal has destroyed 05 % of the tree cover in the region, According to Okidi, before the commercial charcoal deal started in the region, the tree cover was standing at 13. 9 %, but now reduced to 13.4 %.

Okidi revealed that the ministry has already approved a plan for community tree planting in the region, and has signed a memorandum of understanding with both religious and traditional leaders to implement the campaign, adding that the mobilization of funds by the government and partners for the intervention has started.

He added that there is a need to look at the value chain and shift people away from the raw utilization of forest products to finished products saying it is better for individuals and the environment.

Okidi revealed the government has already secured 40 million Euros (166.9 billion Uganda shillings) from the European Union for the proposition of the value chain, where the Northern Region has been identified to take the largest share of the fund.

He further revealed that the fund whose implantation will begin in the financial year 2023/2024 will equally cater for the restoration of the tree cover in the refugee hosting districts in the region where demand for wood fuel is contributing to discriminate tree cutting.

“There is a better alternative to charcoal whose impact isn’t huge on the environment, why can’t our people turn to ethanol when we already have the factory for that in place established in Nwoya?” he asked.

Police respond to compromise with trucks of charcoal at checkpoints

An estimated 20 to 30 trucks of charcoal are transported daily, explaining how the dealers habitually make off with charcoal from the North amidst deployments at the various checkpoints.

As sources revealed, each truck pays 4 million shillings for road clearance, this loosely translates to between 28.8 billion shillings and 43.2 billion shillings lost on the roads annually which dealers divulged that the illicit money is shared between the brokers and the law enforcers.

Fred Enanga, the spokesperson at Uganda Police Force, said the force is ready to investigate and apprehend its personnel deployed along the highways if the evidence of guilt is substantial.

“I can’t speak much at this point but once the evidence and the facts are right, then our team of police professional standard unit at Bukoto will institute an investigation. But remember it’s not only police who are implementing the executive order against this trade” Enanga stated.

Wherever police still wait to institute an investigation on the alleged perpetrators of the crime, the illicit trade thrives in the North where trees have not been spared, the rain-fed agriculture in the region has reduced from two seasons to just one, hence, affecting crop production.

In Gulu City alone, 20 loading camps have been secretly established, the majority of them are within the Western Division where bags of charcoal are ferried into using boda-boda operators before they are transported to Kampala.